Multiple Myeloma: Maintenance Therapy to Prolong Survival and Improve Life after Transplant

Multiple Myeloma: Maintenance Therapy to Prolong Survival and Improve Life after Transplant

Sunday, May 4, 2025

Presenter: Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez, MD, Blood and Marrow Transplant Group of Georgia

Presentation is 36 minutes with 21 minutes of Q & A

Summary: Maintenance therapy is now standard of care treatment in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma. This presentation describes what maintenance therapy is, current medications being utilized for maintenance, and what current clinical trials are hoping to reveal.

Key Points:

- Multiple myeloma cells evolve and become resistant to chemotherapies and treatments overtime. While multiple myeloma is not considered curable, the goal of treatment is to to put patients into remission and maintain that remission for as long as possible.

- Maintenance therapy is standard of care treatment in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. It prolongs overall survival, allows for longer remission durations and time between treatments, and improves overall patient quality of life.

- Lenalidomide remains the preferred drug for maintaining remission, but there are multiple drug options available for specific treatment circumstances and patient needs, and other drugs currently being studied in clinical trials showing promising results.

(02:23): Multiple myeloma occurs because plasma cells have mutated. Their DNA has changed, causing them to divide out of control, and make abnormal proteins called ‘M proteins’ or ‘M spikes’.

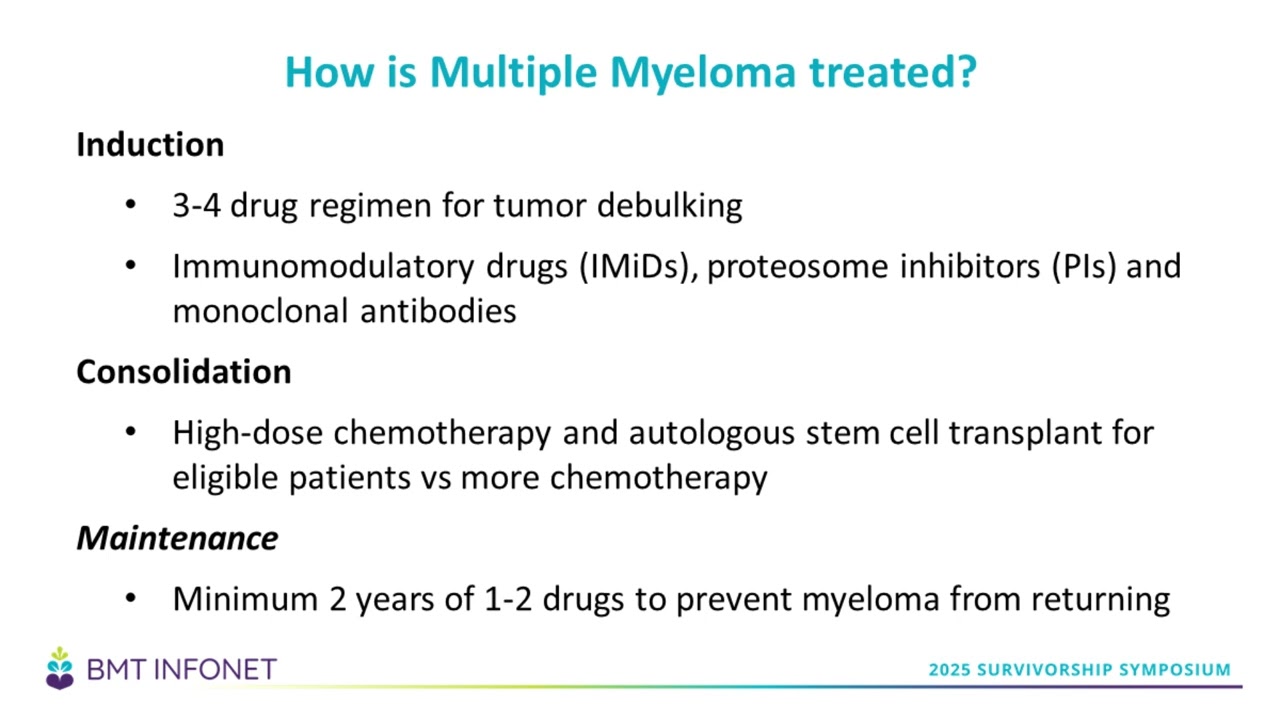

(12:02): There is a three-step process for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: induction, consolidation, and maintenance.

(13:49): There are a couple of terms utilized in multiple myeloma treatment to help classify the response to treatment. These terms include partial response (PR), a very good partial remission (VGPR), complete remission (CR), and stringent complete remission (sCR).

(17:05): Even if patients have achieved complete remission, we still utilize maintenance therapy because it's been shown to prolong survival.

(21:51): There have been multiple studies looking at cost-effectiveness, side effect profile and duration of lenalidomide (Revlimid®) maintenance. The consensus has been that the maximum benefit is usually achieved after three to four years.

(24:47): Recently, there have been trials looking at newer drugs and combination drugs, especially in patients who have high-risk disease.

(26:59): There is a difference between ‘progression-free survival’ and ‘overall survival’.

(29:32): As of now in 2025, lenalidomide (Revlimid®) is the only FDA-approved drug for maintenance, but there are others that are being studied and being used.

(30:45): The reason myeloma cells keep coming back is because of something called ‘clonal evolution’. Essentially, the myeloma cells become smarter over time.

(33:15): Currently, daratumumab (Darzalex®) seems to be the most promising drug in terms of efficacy and side effect profiles.

Transcript of Presentation.

(00:01): (Marla O’Keefe): Welcome to the workshop, Multiple Myeloma: Maintenance Therapy to Prolong Survival and Improve Life after Transplant. My name is Marla O’Keefe, and I will be your moderator for this workshop.

(00:12): Speaker Introduction. It is my pleasure to introduce today's speaker, Dr. Lizamarie Bachier. Dr. Bachier is a board-certified Hematologist-Oncologist and an Attending Physician with the Blood and Marrow Transplant Group of Georgia at Northside Hospital Cancer Institute in Atlanta. Her clinical interests include improving outcomes after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplants, and expanding access to novel cellular therapies for older and frail populations. Please join me in welcoming Dr. Bachier.

(00:47): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): Thank you, everybody, and thank you, Marla, for the introduction. It's a pleasure to be speaking at the symposium today.

(00:58): Overview of Talk. There are a few learning objectives I hope to discuss today. We will learn what multiple myeloma is, how it’s diagnosed and staged, and how we determine what treatment plans to utilize for patients. We’ll talk about maintenance treatment in multiple myeloma including the different treatment strategies used for maintenance, why they are used, and how we should use them.

(01:31): Let's start by reviewing a little bit about what multiple myeloma is. I tell my patients I am a ‘blood cancer doctor’, which means I treat problems in the blood. Multiple myeloma is a type of blood cancer that stems from a specific type of blood cell called the plasma cell.

(01:53): When we look at a specific lab, called a complete blood count (CBC), we can identify different types of cells in the body. There are white blood cells to help fight infection, hemoglobin to carry oxygen, and platelets to help with clotting.

(02:05): There are many different types of white blood cells that fight infection. One is called a ‘plasma cell’. Plasma cells normally make antibodies to help fight infection. When we get sick, plasma cells become activated, make antibodies to fight that infection, and help us feel better.

(02:23): Multiple myeloma occurs because these plasma cells have mutated. Their DNA has changed, causing them to divide out of control, and make abnormal proteins called ‘M proteins’ or ‘M spikes’.

(02:38): Multiple myeloma is more common in African-American patients, as well as male patients, and the median age at diagnosis is 69 years.

(02:49): This slide shows a little schematic about the plasma cells in the body. We can see the plasma cells being made inside the bone marrow. Once again, their normal function is to make antibodies to help fight off infection. When these cells start growing out of control, they make abnormal proteins and abnormal antibodies that are ineffective and cause problems. Because of this overgrowth of plasma cells, it crowds the bone marrow space and begins causing all of the symptoms of multiple myeloma.

(03:36): There was also a mnemonic that we learned in medical school to remember the symptoms of multiple myeloma, known as the ‘CRAB criteria’. The ‘C’ stands for ‘hypercalcemia’ or ‘elevated calcium’. When these plasma cells chew up bone, it releases calcium into the body, and elevated calcium can cause a whole sort of different symptoms. The abnormal proteins can clog up the kidneys, essentially causing the ‘R’-- ‘renal failure’ or abnormal creatinine. The crowding of the bone marrow space blocks other normal cells from being able to grow. This can cause the ‘A’ – anemia. The ‘B’ represents bone pain. Multiple myeloma cells – or these plasma cells – have a predilection for migrating into bone and causing bone fractures and bone pain.

(04:24): Multiple myeloma is diagnosed with blood work, body imaging – either a CT scan or a PET CT scan – and a bone marrow biopsy. These abnormal proteins cause elevated total protein levels, which can be seen in blood work. If someone also has elevated calcium or anemia, we can suspect multiple myeloma and order the specific blood test to see if these abnormal proteins are present in the body.

(04:46): Imaging with a CT scan or PET CT is crucial in diagnosing multiple myeloma, to see if there is evidence of these proliferating myeloma cells.

(05:00): A bone marrow biopsy is a diagnostic test that looks directly at the bone marrow to assess what these plasma cells are doing, and what percentage of plasma cells are present in the bone marrow. We can utilize these samples to send a lot of specific genetic tests, and be able to stage the myeloma and identify how aggressive and progressed the myeloma is.

(05:27): There are three different stages of myeloma depending on how much disease is present and if certain genetic mutations are present.

(05:34): This slide has a picture of how plasma cells look in the bone marrow space, and a picture of a PET CT of an individual with many highlighted black spots in their bones. Primarily, these represent proliferating myeloma cells, and they light up on PET CT imaging. We can use a bone marrow biopsy to look at the percentage of plasma cells, and this percentage is used as part of the criteria to assess disease progression and the response to treatment.

(06:12): When we talk about how multiple myeloma is staged, it is very important to note a distinction between how blood cancers are staged and how solid tumors are staged. When we have a solid tumor – for example, breast cancer – these tumors have a stage one, two, three, and four. These stages are based on how big the tumor might be, and whether it is invading adjacent structures or nearby organs and tissues.

(06:44): The staging of blood cancers is different. In myeloma specifically, there are only three stages based on how much disease is present in the body. While a solid tumor might be confined to an organ or specific space, the blood migrates throughout the whole body. Our blood is essentially circulating throughout all of our tissues, so it really cannot be staged in the same way as a solid tumor.

(07:20): The stages used for multiple myeloma are based on how much disease is present. This criteria is called the Revised International Staging System (R-ISS). There are three stages, all based upon how much of an abnormal protein – called ‘beta 2-microglobulin’ – is produced in the body, and how it is affecting your albumin.

(07:45): Albumin is a normal protein that our liver produces, and is a measure of how well-nourished we are. When multiple myeloma occurs, there is such an overproduction of those M-protein cells, that albumin production goes down. In multiple myeloma, your albumin levels will usually go down and your beta 2-microglobulin levels which go up. The numerical values of those two tests – the albumin and the beta 2-microglobulin – will indicate if it is stage one, two or three.

(08:28): Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) is another test we can see in lab work, and is another predictor of the stage of myeloma as well. LDH measures the amount of cell turnover – if there are a lot of cells in the body, there's a lot of production of LDH. Therefore, if there are a lot of multiple myeloma cells, LDH goes up and that essentially means that there's more tumor burden.

(08:54): Hematologists-oncologists assess the risk stratification of the myeloma by looking at its cytogenetics – or its DNA and molecular tests – and also utilize these tests to predict the response to therapy. Your body’s DNA essentially makes up the building blocks of all the cells in our body. Multiple myeloma cells also have DNA in the cell nucleus, but this DNA inside these plasma cells has mutated.

(09:31): A very important test that is sent from the bone marrow is chromosome testing, or something called Fluorescence In Situ Hybridization (FISH) testing. I'll talk about this more in the Q&A – as I can already see some questions about predictors of response to therapy and cytogenetics – but these FISH studies have a lot to do with that.

(09:52): There are some mutations – or changes – in the DNA that can predict if the disease will be more or less aggressive. We also use these chromosome changes when we talk about staging multiple myeloma.

(10:08): Now that we've discussed some background regarding how we diagnose and stage multiple myeloma, let's move on to treatment and maintenance therapy. Let’s begin with the goals of treatment in multiple myeloma.

(10:27): When somebody is newly diagnosed with multiple myeloma, I explain to them that while it is not considered curable, it is highly treatable. The goal of treatment is to induce remission. Remission occurs when we can no longer see myeloma cells in your bone marrow, and we try to maintain that remission for as long as possible. Remission does not mean the myeloma is cured, but it is under control, and our goal is to have patients stay in remission for 10 to 15 years, instead of needing treatment every year.

(11:17): Myeloma treatment looks like a roller coaster. Patients will be newly diagnosed, they'll get treated, the myeloma will go away. Eventually, the myeloma will return months or years later, the patient will need to be treated again, they will go into remission again, the myeloma will eventually relapse again, the patient will undergo treatment, and it's like this roller coaster cycle of myeloma relapsing and remitting.

(11:40): The best chance at having a prolonged remission duration is after the first treatment, because the myeloma cells have not yet seen any therapies, and are therefore not smart enough to escape or become resistant to chemotherapy.

(12:02): There is a three-step process for newly diagnosed multiple myeloma; induction, consolidation, and maintenance. Induction is the initial chemotherapy that is prescribed to get rid of as much myeloma as possible. I sometimes refer to induction as ‘tumor debulking’.

(12:22): The standard of care induction regimen usually consists of three to four drugs. This includes an immunomodulatory drug – usually lenalidomide (Revlimid), – a proteasome inhibitor – usually Velcade, and a CD-38 antibody called daratumumab (Darzalex). High dose steroids are generally prescribed as well. This induction therapy will be given for four to six cycles with the goal of eradicating as much of the disease as possible. About 70% of the time, patients will induce a very good partial remission (VGPR) or better after induction.

(13:01): The next phase of treatment is consolidation. The goal of consolidation is to deepen the response that you've achieved with your induction, and ultimately achieve remission. Consolidation includes either more high-dose chemotherapy, or an autologous transplant for patients who are candidates for one.

(13:32): Finally, patients enter the maintenance phase – which usually lasts at least two years – and includes one to two drugs used to prevent the myeloma from returning.

(13:49): There are a couple of terms utilized in multiple myeloma treatment to help classify the response to treatment. These terms include partial response (PR), a very good partial remission (VGPR), complete remission (CR), and stringent complete remission (sCR). The response criteria is based on how much disease is left over compared to when they were first diagnosed.

(14:30): For example, if a person had 50% plasma cells in their bone marrow and an M-spike of four grams per deciliter at diagnosis, and they have a 50% reduction, they're in a partial remission (PR). If they have a 90% or greater reduction, they are in very good partial remission (VGPR).

(14:53): Complete remission (CR) means you don't see any abnormal proteins in the blood and you have less than 5% plasma cells in the bone marrow. When we talk about stringent CR (sCR), there are no abnormal myeloma proteins in the blood, you don't have any clonal plasma cells evident in your bone marrow biopsies, and you have a normal ratio of free light chains – a protein made by plasma cells – in the blood.

(15:13): These bone marrow biopsies are important because they are used to determine response criteria, and help guide the hematologist-oncologist’s decisions regarding treatment – including consolidation and maintenance therapy. If a VGPR is achieved after induction, perhaps consolidation will move that patient into a CR, and maintenance treatment might help keep the patient in complete remission for a longer period of time.

(15:53): Now, let's turn our focus to the maintenance phase of multiple myeloma treatment. Maintenance therapy is chemotherapy that's given after consolidation treatment. Maintenance therapy is given for several years in patients to prevent disease progression and death.

(16:21): Currently, the preferred maintenance therapy drug is lenalidomide (Revlimid), but there are other drugs that have been studied and used that we’ll discuss including bortezomib (Velcade), ixazomib (Ninlaro), daratumumab (Darzalex), and carfilzomib (Kyprolis).

(17:05): Even if patients have achieved complete remission, we still utilize maintenance therapy because it's been shown to prolong survival. Even at a microscopic level, our methods of detecting myeloma are not perfect. There might be remaining myeloma cells in the body after induction and consolidation, and we can think of maintenance as soldiers surveying the blood, ensuring the myeloma cells do not come back. The goal is that a person on maintenance therapy will stay in remission and live longer, because they don't have a lot of tumor burden and these drugs help keep the myeloma away for a longer period of time. Once again, maintenance therapy is usually only one or two drugs, and they all have very manageable side effects.

(18:32): Let’s discuss a couple of different drugs that are used in maintenance therapy, including why these drugs have been selected, how we decide which drug to use, and how we get them. The first drug is lenalidomide (Revlimid), which is currently the most common one, and the drug we’ve been using the longest in maintenance therapy.

(18:48): A lot of this data is based on trials that were done in 2005. It might not seem like that long ago, but this data is 20-25 years old. These are strategies that we've been using for the last 15-plus years, with some changes and evolution of treatment along the way.

(19:16): Revlimid is an immunomodulatory drug – it changes your immune response to better fight off and prevent the disease. Prior to Revlimid was this drug called thalidomide. Thalidomide came with a lot of issues, and you might have heard stories of the thalidomide babies. Essentially, back in the 1990s thalidomide was a drug that was used very frequently in multiple myeloma, but once Revlimid came along, we transitioned to using it instead.

(19:52): One of the pivotal trials was the CALGB 100104 or IFM 2005-02 that began in 2005. This was a randomized trial in newly diagnosed patients, who had gone through induction, received an autologous stem cell transplant, and were then randomized to either receive lenalidomide maintenance or a placebo.

(20:17): Prior to this, we were doing all sorts of different things, and were using cytotoxic chemotherapy for induction, without any maintenance or immunomodulatory drugs afterwards. Some of these regimens included melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide for induction, or a combination of bortezomib (Velcade), anthracyclines, and dexamethasone. As immunomodulatory drugs were developed, we started assessing their effectiveness in helping prolong survival rates.

(21:02): If you look at these survival curves on the graph, patients who received Revlimid lived longer and did better than those who did not receive Revlimid. Again, this was a randomized Phase III trial – multiple patients were treated exactly the same, except for whether or not they received maintenance Revlimid. Those that received maintenance therapy lived longer, so it is because of this trial that Revlimid became the standard of care in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma.

(21:51): Since this trial, there have been multiple studies looking at cost-effectiveness, side effect profile and duration of Revlimid maintenance. The consensus has been that the maximum benefit is usually achieved after three to four years. After that, the benefit tapers away.

(22:11): For the most part, I tell patients to expect to be on Revlimid for at least two years – preferably three or four – and likely not more than five. We constantly assess how they are tolerating it and help manage side effects, but usually it is very well tolerated.

(22:36): Since that trial came out, different drugs have been tested for its effectiveness in maintenance therapy. Another drug that was considered was bortezomib (Velcade). A couple trials assessed the use of Velcade in both transplant-eligible and transplant-ineligible patients. They showed that using Velcade did improve progression-free survival without necessarily affecting quality of life. The study did not show a longer survival benefit, but they were also comparing it to thalidomide maintenance, not Revlimid maintenance. Patients who got Velcade did better than those who did not get Velcade, but this was not compared to the standard of care, Revlimid.

(23:14): Nonetheless, because of this trial and the difference in survival curves between the Velcade maintenance versus not, Velcade became a second alternative for maintenance strategies after initial induction.

(23:48): Peripheral neuropathy and a cumbersome administration schedule are the main issues we see with Velcade. Velcade is administered every other week as an injection for at least two years. Peripheral neuropathy side effects can be pretty significant for patients as well, and has caused significant morbidity in multiple myeloma patients. This makes Velcade less ideal when compared to Revlimid, as Revlimid is a pill, allowing more scheduling freedom and less severe side effects.

(24:47): Recently, there have been trials looking at newer drugs and combination drugs, especially in patients who have high-risk disease. Carfilzomib (Kyprolis) was developed in 2014. The FORTE trial compared carfilzomib (Kyprolis) and Revlimid in patients who were transplant eligible, newly diagnosed and had high-risk disease. One group had induction with carfilzomib (Kyprolis), Revlimid, and dexamethasone (KRd). The other group had induction with carfilzomib (Kyprolis), Cytoxan, and dexamethasone (KCd). Both groups had an autologous transplant. Then their consolidation was either Kyprolis plus Revlimid or Revlimid alone.

(25:46): There was an improvement in progression-free survival rates in the Kyprolis plus Revlimid group, but this improvement came with a cost. The carfilzomib group had more adverse events – or side effects – than those that were on Revlimid alone. The thought process that arose from this trial is that while Kyprolis is a good maintenance strategy, it should be reserved for patients who have high-risk cytogenetics and high risk of relapse.

(26:22): Ixazomib (Ninlaro) is an oral pill that is a proteasome inhibitor, so we can think of it as Velcade's cousin. Velcade is the injection, and Ninlaro is a pill. Ninlaro has also been approved in patients with multiple myeloma. In the TOURMALINE trial, it was tested as a maintenance strategy in patients after autologous stem cell transplant. It improved progression-free survival, but there was no change in overall survival.

(26:59): Let me take a moment to differentiate between ‘progression-free survival’ and ‘overall survival’. Progression-free survival is the time after treatment where no other treatments are needed. For example, this might be the time between when maintenance began, to the time that relapse occurred and treatment was needed again. Patients with multiple myeloma have many treatment options these days – even if relapse occurs, there are many more treatment options and therapies available. I had a patient not that long ago who was on her 11th line of therapy. Overall survival is essentially how long you live – so it's time from starting maintenance to death.

(27:44): Until the GRIFFIN trial, the only trial that had shown an improvement in overall survival was the trial with lenalidomide. The GRIFFIN trial took patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma who had received transplants in consolidation, and gave them daratumumab (Darzalex) in addition to lenalidomide. These patients had an improvement in progression-free survival, and I believe there was an overall survival benefit as well.

(27:56): The GRIFFIN trial really changed the induction treatment plan for patients with multiple myeloma, as it took the standard of care – lenalidomide, bortezomib (Velcade), and dexamethasone – and added the drug daratumumab (Darzalex).

(28:31): Currently, there is an ongoing trial called the DRAMATIC trial that is essentially looking at induction, consolidation, and maintenance with daratumumab (Darzalex) and Revlimid versus Revlimid alone. We're still waiting to see how that trial goes, but it does seem that the addition of Darzalex with Revlimid does not significantly increase adverse events or side effects, and does have a positive impact on survival – both progression-free survival and overall survival. While I have not yet seen a significant change in incorporating this dual-drug combination, I do know it is useful for a subset of patients, especially those that have higher risk myeloma.

(29:32): As of now in 2025, lenalidomide (Revlimid) is the only FDA-approved drug for maintenance, but there are others that are being studied and being used. The use of drug combinations – such as carfilzomib and lenalidomide, or daratumumab and lenalidomide – could be beneficial in patients who have a high risk of relapse.

(30:07): While there is no consensus on when to stop maintenance, many studies suggest that there's no benefit after three to four years. It would be useful to have tools to predict when it is safe to stop maintenance. Many academic institutions are working with platforms – such as next-generation sequencing – which are much more specific and sensitive tools to see if there really is any residual disease left. This information would help indicate when it would be safe to stop maintenance.

(30:45): The reason myeloma cells keep coming back is because of something called ‘clonal evolution’. Essentially, the myeloma cells become smarter over time. Usually, the first period of remission tends to be the longest. With each subsequent relapse, the remission duration is shorter because the cells continue to evolve, continue to become resistant to treatment, and become much harder to keep the disease away. A lot of thought has gone into looking at these next-generation sequencing platforms, in hopes that they could better indicate if someone is minimal residual disease (MRD) negative. Utilizing these more sophisticated tools, we'd be more accurately able to tell whether or not there is any detectable disease, and allow patients to stay in remission longer.

(31:53): Maintenance therapy can be expensive, but the reality is that you are trading one cost for another. Essentially, you're trading the cost of maintenance therapy for the cost of myeloma treatment when it relapses. Despite the higher upfront cost, the goal of maintenance is to prevent financial burden down the line by preventing relapse and the need for treatment.

(32:21): Usually, the side effects are very manageable and can be mitigated with dose modifications. As an example, lenalidomide has a risk of secondary skin cancers, low blood counts, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea. We discussed how bortezomib (Velcade®) causes peripheral neuropathy. Carfilzomib (Kyprolis®) has a lot of cardio-toxicities. These are all things that your hematologist should be discussing with you at every follow-up appointment, to ensure you are tolerating the drug well and assess if any dose modifications need to be made.

(33:15): Currently, daratumumab (Darzalex®) seems to be the most promising drug in terms of efficacy and side effect profiles. Darzalex® is a CD38 targeting antibody therapy. CD38 is a protein on the surface of plasma cells, and Darzalex® works by attaching to this protein on the plasma cells and essentially calling all other immune cells to kill it. It is very well tolerated, and it can be given both as an infusion and as an injection. Once you go into maintenance with Darzalex®, the dosing schedule also changes to where a patient might be getting Darzalex® just once a month. This is a much more reasonable and accessible treatment schedule for patients.

(34:19): This slide is looking at a real-world cost analysis of lenalidomide (Revlimid®) maintenance, assessing the inpatient, outpatient and pharmacy costs in time intervals of 0-12 months, 12-24 months, and 24-36 months. You can see that as time goes by, while the lenalidomide group has a higher cost overall, those costs are split more towards pharmacy, and less towards inpatient. This might indicate that patients who don't get maintenance therapy might have higher inpatient or outpatient expenses because of relapse compared to those on maintenance.

(35:08): Ultimately, deciding what treatment to use should be made with your hematologist-oncologist, and is very individualized. It involves looking at the holistic picture – looking at patient preferences, their physical activity levels, work productivity, any comorbidities they might have, quality of life, disease or symptom control, treatment related toxicities, treatment convenience, and financial burden. It is a decision that is made together, with all the pros and cons taken into account.

(35:40): Conclusion. To conclude, maintenance therapy is standard of care treatment in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients. It improves outcomes including prolonging overall survival, longer remission durations and time between treatments, and overall patient quality of life. Lenalidomide remains the preferred agent of choice, but there are multiple options available for specific treatment circumstances and patient needs. With that, I’ll turn it over to Marla O’Keefe.

Question and Answer

(36:27): (Marla O’Keefe): Thank you, Dr. Bachier, for the excellent presentation. We'll now get to some questions.

(36:43): Are there any predictive biomarkers to determine who will benefit from Melphalan and how deep and durable the response may be? Some patients get zero benefit?

(36:55): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): Yes, I alluded to this previously when I talked about fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) testing. There are not necessarily specific biomarkers, but there are cytogenetic changes. Through different genetic studies, we have identified cytogenetic changes that can predict resistance to chemotherapy.

(37:23): Melphalan is a common chemotherapy used during treatment. It is an alkylator, and essentially works by causing DNA to damage malignant cells. For example, patients who have deletion 17p or TP53 mutations will have a lot of resistance to conventional chemotherapy. That's why in specific patient populations, more targeted therapies, biological therapies or immunotherapies are preferred over conventional cytotoxic therapy.

(37:55): There is still value in cytoreduction with melphalan, but yes – patients who have these high-risk cytogenetics tend to be more chemo-resistant. While there's no specific biomarker, there are cytogenetic factors that we take into consideration.

(38:17): (Marla O’Keefe): Are there times when you feel it is safe to discontinue maintenance?

(38:27): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): Yes. While not everybody has access to these next-generation sequencing tests, we can use this test as a predictor for stopping therapy. Patients who had a negative next-generation sequencing (NGS) have had maintenance discontinued.

(38:43): I will also say that if I have a patient who has been in a complete remission for three or four years, I feel that it's safe to stop. I always make the caveat that it will still probably come back, but after three to four years, if a patient has maintained a complete remission – meaning they don't have any M-spike and their bone marrow has less than 5% plasma cells – I do stop their maintenance.

(39:14): (Marla O’Keefe): Upon relapse after transplant, should you immediately undergo another transplant, or is there medication that's okay to take first?

(39:25): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): It really depends on when you relapse and is very patient specific. For example, somebody who relapses two to seven years after transplant means they benefited from the transplant, and therefore we might consider a second transplant in that case.

(39:41): Now chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T-cell) therapy is available as a second line in patients who relapse after transplant, and we take into account how soon they relapsed after transplant. If relapse occurs within a year of transplant, the second transplant is unlikely to provide any benefit. At that point, we would move towards other cellular therapies like CAR T-cell therapy.

(40:06): Timing between transplant and relapsing, and other factors like the patient's age, and other health conditions are also considered. The bottom line is, we will consider a second transplant if the first transplant was effective – meaning it provided two or more years of remission.

(40:29): (Marla O’Keefe): If the first line of treatment fails, what are the factors that are important to consider in regards to CAR T for multiple myeloma?

(40:42): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): So again, CAR T-cell therapy is currently approved as a second line therapy. Specifically, ciltacabtagene autoleucel (CARVYKTI) is the therapy that's approved for multiple myeloma.

(40:51): To be a candidate for CAR T-cell therapy, a person must be able to manage their activities of daily living – meaning they can shower independently, eat independently and care for themselves. We also test organ functions to ensure they will be able to handle the treatment. Prior to getting the CAR T-cell therapy, there is three days of chemotherapy called ‘lymphodepleting chemotherapy’. This chemotherapy can affect the heart, lungs, and kidneys. While they don’t have to be perfect, the patient must be in a relatively normal range for things such as heart and kidney function.

(41:36): Then, they must have caregiver support. CAR T-cell is much like transplants in that it requires a lot of caregiver support to take them to infusion appointments, monitor side effects and ensure the patient is doing okay. An appointed caregiver is a very important factor.

(41:55): From a disease standpoint, we do CAR T-cell therapy even in patients who are actively relapsing, but patients who have very rapidly progressive disease might not have time to wait for the CAR T manufacturing process. So the disease kinetics and the speed in which the disease is progressing is another factor considered.

(42:19): This brings up a good point that these decisions about CAR T and transplants should be made by a transplant doctor and a CAR T doctor. If a patient ever has any questions about whether or not they're a candidate for CAR T, they really should ask their local oncologist to refer them to a cellular therapy physician, because it is a cellular therapy specialist that needs to be making these decisions, not just a local oncologist.

(42:52): (Marla O’Keefe): What maintenance meds are used in post-CAR T therapy?

(43:01): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): When we give CAR T, it’s supposed to be a singular therapy, so none of the trials had maintenance strategies post-CAR T. Once CAR T-cells are manufactured and re-infused, the cells actively live in the patient's body, and persist for some time to allow an ongoing response. The cells continue working in the body.

(43:44): As of May 4th, 2025, there's no maintenance after CAR T. That might change because CAR T-cell therapy isn't perfect, and we know these cells don't last forever. It'll be interesting to see what the future holds, and if strategies arise to essentially boost these CAR T-cells to keep them working in the body. But as of now, there's no maintenance therapy after CAR T.

(44:21): (Marla O’Keefe): My oncologist has said that of all the myeloma treatments that are currently being developed, the most helpful might be trispecifics. How much more effective do you think those will be? Are you hopeful that they will be better than bispecifics? Do you know a potential timeline for when they might become available?

(44:47): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): There are many different cells in the body; one of them being T-cells which are in charge of killing cells that do not belong, like myeloma cells. Bispecific antibodies are antibodies that have two signals; one to signal T-cells, and another to signal myeloma cells. When this antibody is administered, it brings the T-cells and myeloma cells together and allows the T-cells to kill the myeloma cells. Currently, there are bispecific antibodies against two tumor markers within multiple myeloma. One is the B-cell maturation antigen (BCMA), and the other one is called ‘GPRC5D.’ Combinations of bispecifics are currently being used in treatment.

(45:48): The thought process behind trispecifics is that you have more tumor antigens to target. If you have more signals to find more myeloma cells, you can potentially bring more T-cells to fight and attack them. However, multiple myeloma cells continue to evolve and change after treatments. If they're being attacked via BCMA or GPRC5D markers, they will ‘shut down’ the BCMA or GPRC5D, and become resistant to drugs against BCMA or GPRC5D.

(46:51): With trispecifics, the thought is that you're exerting pressure on different sites of the myeloma cells, and don’t really give the cells a chance to adapt and regulate a specific receptor. This is still a few years down the line, and I would estimate we will see more of these probably in two years or so.

(47:20): A developing treatment I'm actually more excited about than trispecifics is CAR T-cells dual targeting antigen. For example, CAR-T cells manufactured to fight against BCMA and CD19, not just CD19. The whole idea is that you're trying to attack the myeloma cells on two fronts to prevent the myeloma from becoming resistant to one or the other.

(47:44): (Marla O’Keefe): Is a PET CT scan for multiple myeloma relying on the same fact that multiple myeloma has much higher uptake of glucose than normal plasma cells? Do we know how much higher the uptake in glucose is in general?

(48:05): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): Yes, the reason PET CTs work is because cancer cells divide more rapidly, and therefore take up more glucose than regular cells. That's exactly how PET CT works. The myeloma cells pick up the glucose, causing them to light up on the scans. In terms of how much more, it depends on how active and how proliferative they are. As an example, the baseline mean uptake of the liver is a number of around 2. Normally run-of-the-mill myeloma cells will have an uptake between 7 and 12. If the cells are highly proliferative, it can be more than 12.

(49:09): (Marla O’Keefe): If 10 milligrams of lenalidomide caused definite IBS after one year, would Revlimid five milligrams daily be an option?

(49:20): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): Absolutely. Earlier I talked about dose modifications, and this is exactly that. Initial studies with lenalidomide (Revlimid), were using a dose of 10 milligrams. We know that not everybody needs 10 milligrams, and if they can only tolerate five or even two and a half, that's better than zero.

(49:44): If you don't tolerate 10 milligrams, you should go down to five. If you don't tolerate five, you can try five every other day, or you can try two and a half. All of these dose modifications are made in conjunction with your oncologist, never try to change the dosing on your own. I encourage you to talk to your oncologist about the symptoms you are having and start a conversation about modifying your dose. It is absolutely appropriate to do so.

(50:17): (Marla O’Keefe): I would like to know more about extramedullary disease; how and why do the myeloma cells leave the bone marrow and travel elsewhere? The big question is what does the future hold for me?

(50:31): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): When we talk about extramedullary disease, it's essentially plasma cells migrating to places they are not supposed to be. Plasma cells should be in the blood or the bone marrow. But plasma cells can migrate out to places – such as the liver or soft tissues – due to homing signals that are not entirely understood.

(50:58): One treatment option for extramedullary disease is localized radiation to a specific area. Extramedullary disease tends to be a little bit more resistant to conventional treatment, so when we talk about responses, they don't generally include extramedullary responses. It does respond, it just responds less than the disease inside your bones or inside the blood.

(51:46): (Marla O’Keefe): You did not mention the particular side effects associated with lenalidomide (Revlimid) or daratumumab (Darzalex). Can you give us some of those?

(51:58): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): Sure. Lenalidomide’s main side effects are nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, rashes, and low blood counts. Lenalidomide can cause neutropenia – meaning your neutrophil counts lower. Over time, there is a risk of secondary cancers – more specifically skin cancers. Again, with dose modifications, these side effects go down.

(52:23): Side effects seen with Darzalex include mild GI symptoms or abnormal blood counts, but not a significant amount. Infusion reactions are most common with Darzalex and are associated with getting the injection itself. This might mean some redness of the skin at the injection site, or hives. Darzalex is definitely very well tolerated.

(52:51): (Marla O’Keefe): How impactful is deletion of chromosome 13?

(52:58): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): Deletion 13 is a standard within cytogenetic testing in multiple myeloma – it is considered standard risk, not high risk.

(53:20): (Marla O’Keefe): Has there been any studies comparing the efficacy between generic versus brand name medications?

(53:27): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): They are both equally effective, however some patients tend to report more side effects with the generic version. But efficacy is the same.

(53:54): (Marla O’Keefe): My son is 26 and has multiple myeloma and amyloidosis. Would the myeloma have possibly caused the amyloidosis?

(54:03): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): Yes. Not all amyloid comes from multiple myeloma, but if you have multiple myeloma and amyloid, then yes, your amyloid came from your multiple myeloma. Amyloid occurs when the abnormal M-spikes are deposited in tissues. This doesn't always happen – so you can have multiple myeloma without amyloid, and you can have multiple myeloma with amyloid.

(54:38): (Marla O’Keefe): Someone wanted clarification on an earlier slide. They didn't think that DRVD was considered chemo, but your slide earlier called the maintenance drugs chemo?

(54:51): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): They are correct, those drugs are not technically chemotherapy. For the convenience of this talk, I called all drugs prescribed by an oncologist ‘chemotherapy’. Lenalidomide is an immunomodulatory drug and daratumumab is an immunotherapy.

(55:12): More specifically when we think about conventional chemotherapy, these are cytotoxic drugs like melphalan and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan®). But they are correct, those are technically biologic therapies, not chemotherapies.

(55:35): (Marla O’Keefe): Is there anything that an individual can do to lessen bone pain?

(55:47): (Dr. Lizamarie Bachier-Rodriguez): It really depends on why they're having bone pain. If they're having bone pain because they have active disease, then hopefully treatment of the myeloma will help ease that bone pain. If their disease is in remission and it's because of nerve damage – either from the disease or from the consequences of chemotherapy – then we can utilize different drugs to help manage the pain. Drugs like gabapentin or pregabalin (Lyrica) really target neuropathic pain, while bone pain is better controlled with non-opiates and opiates. If the pain is because of a large tumor mass, we can consider palliative radiation.

(56:27): Myeloma can cause pain, and it is important we do not forget about that. There tends to be a lot of stigma around the use of different pain medications, but I would encourage patients to be proactive and talk to their doctor. Perhaps a dedicated pain team can get involved to help come up with a plan that involves a combination of treatments.

(57:14): (Marla O’Keefe): Closing. Thank you for those answers, and for this wonderful presentation, Dr. Bachier. On behalf of BMT InfoNet, we'd like to thank you, and thank the audience, for their excellent questions. Please contact BMT InfoNet if we can help you in any way.