Robert Henslin

Redding, California

Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia

Transplanted in 2009

Many thanks to the American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy for helping us share Robert’s story.

Can you tell us about what it was like to be diagnosed with leukemia as a young, newly married man?

In 1989, about six months after getting married, I started feeling like I had a cold or flu. It got worse and worse until I had to take a medical leave from work. I was at home, not feeling well when a liver specialist I’d seen called and said, “Admit yourself to Huntington Hospital today.” That was when something hit me. I was in the deep weeds.

A bone marrow aspiration revealed an extremely elevated white blood cell count. My then-wife was working as an oncology nurse at the time; she suspected what it was. However, the doctors at Huntington Hospital couldn’t offer us a definitive diagnosis. After seven errant diagnoses, acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) was finally confirmed at City of Hope hospital, where I began treatment. Their approach was, ‘let’s see if we can get you into remission in six weeks’.

After only five weeks, my oncologist, a wonderful doctor – Dr. Nade – came into the room. She called me ‘Big Bob.’ She said, ‘There’s no trace of disease in your body, and now we have to keep it this way.’ In reality, that’s a hard thing to do. Most people come out of their first remission in 2-5 years. But I went for 19 and a half years!

That is astonishing, 19 years of remission without a transplant. Did you expect that outcome? And can you tell us what it was like for you and your family during those years?

Those 19 years were wonderful, but also plagued by what my wife and I called the monkey on our backs. We used to wonder: How deeply is the monkey sleeping? And, if he wakes up, is he going to have an attitude problem? But in the meantime, we lived our lives.

In 1992, we learned that my wife was pregnant. I took it as the Lord saying, “I’m going to bless you with a daughter, and it will change your whole dynamic.” We moved to Sunnyvale. I was growing my graphic design business and then, two years later, our second daughter Kristen was born.

I consider both my daughters to be miracles, as my wife and I were told that having children was most likely not possible. The ravages of chemotherapy typically put an end to such dreams. But despite that ominous warning, we were blessed with two healthy, beautiful daughters.

We bought a house in San Jose and had a great life in the South Bay! My daughters were both on dance teams and they both played soccer. We went from fearing we wouldn’t be able to have kids, to suddenly having these two beautiful girls. It was amazing. And, the girls’ whole posse of friends hung out at our house. They all called me “Papa Henslin.”

Then in October of 2008 – when my youngest daughter was a freshman in high school and my eldest was a junior – the monkey came back. With a vengeance.

I’d gone to Kaiser for a regular checkup. At the appointment, my doctor said, “By the way, why don’t you stop off and get a CBC?” Two hours later, she called and said, “Robert, how are you feeling?” I knew right away. My wife looked into the room while I was on the phone, I remember just making a thumbs down. And I could see this wave of dread hit her.

Almost instantly, the line from the doctors was, ‘You’re gonna need a transplant to have any chance of survival’. Suddenly, my girls are going to school with their everyday worries and also wondering whether their dad was going to die. The first time I got sick was just Michele and me; it was simpler. But now we had two daughters and a mortgage and dogs and cats.

That is a lot of responsibility to carry into an experience like transplant. Did you have a sense of what to expect? Were you hopeful?

The whole idea of a transplant was scary. I had antiquated, all-bad images. My wife, having worked in oncology in the past, was a little more familiar. When we went to the orientation session, run by a nurse who worked on the unit, we were all given these 3-inch-thick binders. Those binders were an essential part of getting a foothold on the beast called transplant.

All this took place at Stanford, where my case was referred after I relapsed. At Stanford, every potential transplant goes before a round table of doctors for consideration. My doctor later told me that there was debate about me. A few doctors said, “Listen, this patient went 19.5 years in his first remission. Who is to say he couldn’t go another 20 years treated with chemo again?” But my doctor made my case, and they took me.

And, once you were accepted for transplant, did you have a donor ready?

Initially, I was told they’d found something like 800 potential donors. At the next meeting, it was down to 200. Finally, my doctor told me, “We haven’t found a single perfect donor for you…we found FOUR! Four perfect matches.”

They selected a 20-year-old man from Germany. He had signed on to the bone marrow donor registry during high school, hoping to be a match for a teacher diagnosed with Aplastic Anemia. He was not a match for his teacher. But two years later, he received word he matched another person on the planet, in another country, and he agreed to donate to a stranger. We have not yet met face-to-face, but that is a day I continue to hope will happen. It would be the best day of my life. I don’t know what I would say to him beyond, “Thank you for saving my life.”

Was transplant as daunting as you feared it might be? Or less so? What was your experience?

My transplant experience itself was fairly typical. My stay in the unit was 48 days. At some point, I’m picking my meals, thinking, ‘I like Jello, but does my donor like Jello?’ Or, ‘I like roast beef, but what does my donor feel about roast beef?’ The nurses reassured me that this kind of thinking was normal. The nurses really helped me get through by taking one day at a time.

I was finally released on a beautiful spring day in March 2009. I breathed in fresh air for the first time in 48 days. I felt the rush of cool against my face. Tears welled up in my eyes as I realized I had survived.

As my wife went to get our car, I sat under these big, puffy white cumulus clouds in a blue sky, thinking ‘I made it.’ The sky was never as blue, the clouds were never as white, the grass was never as green, even the showering water sound of a nearby fountain was spectacular. It was the best ten minutes of my life.

As my wife and I drove away, I was overwhelmed with emotion and could not stop the tears from flowing. I had held much of that deep inside for 48 days. Letting the tears flow and resting in the reality that I was headed home to be with my wife and daughters provided a profound sense of hope and peace I have never experienced since.

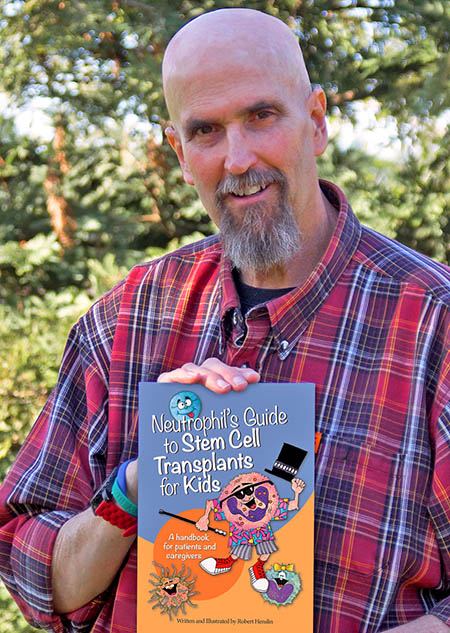

To date, you’ve written four books chronicling your experience of transplant, and beyond: three personal memoirs and a book to help kids navigate their stem cell transplant. What’s motivated you to write through, and about, such difficult material?

All these books are about sharing a story to help others so that they can know they are not alone. One family wrote to me and said, “We want to thank you for writing this book because our aunt was just diagnosed with ALL, and your book will help us support her.”

Can you describe each book, and tell us a little bit about the aims of each?

All are available through Amazon as well as at After the Fire Press.

My first book is about my original diagnosis with ALL and getting through that. It’s called, But I Was in Such a Good Mood This Morning.

My first book is about my original diagnosis with ALL and getting through that. It’s called, But I Was in Such a Good Mood This Morning.

The second book, When You See the Cows, Make a Left, is about me looking for greener pastures, post-divorce, and finding solace in a new community.

My third book –Neutrophil's Guide to Stem Cell Transplants for Kids – is an illustrated, upbeat and compassionate guide to help kids 9-12 and their adult caregivers navigate transplant. It was spawned by a conversation with my nurses at Stanford, who encouraged me to write a story for children. This gave me a chance to write from a character’s point of view, empathize with sick kids, and give them hope.

write a story for children. This gave me a chance to write from a character’s point of view, empathize with sick kids, and give them hope.

My fourth book, Losing My Brother, is about losing my one and only older brother to suicide, in 2016.

Each of these books is written with the hope that my story can reach someone else, in whatever circumstances they find themselves, with empathy. Turning a journal into a book that people might take courage from is such an opportunity.

Thank you for all you’ve done to make your stories meaningful for others. Finally, can you tell us a little about how you’re doing these days, including your health and what brings you joy?

Well, I have a granddaughter now, Marley, she’s in the 3rd grade and getting text pictures of her – that’s a joy!

In terms of my recovery, it’s complex. After the transplant, I dealt with acute GVHD in my liver and my eyes, plus chronic cellulitis infections in my legs, particularly my left leg. The complications persisted for several years. I didn’t get full leg strength back for almost five years.

I’m stronger now. I’ve been dealing with skin cancer now for 13 years, caused by a combination of my eternally compromised immune system and a medication — an antifungal, Voriconazole — that can make one susceptible to developing squamous cell carcinoma. I’m being successfully treated so far.

I’m stronger now. I’ve been dealing with skin cancer now for 13 years, caused by a combination of my eternally compromised immune system and a medication — an antifungal, Voriconazole — that can make one susceptible to developing squamous cell carcinoma. I’m being successfully treated so far.

Beyond writing, I enjoy rocketry and all things aerospace. My late brother and I used to build and fly model rockets as kids. I got back into the hobby with my daughters in 2005. My home office is a testament; I have rockets adorning most horizontal surfaces!

I also pursue my life-long love of photography, primarily shooting images of nature. After my transplant, I came to appreciate—in a new way—the beauty all around me. Photography helps me embrace that beauty, whatever the subject—flowers, snow-capped mountains, rolling farmland, sunsets, and so much more. My “photo safaris” remind me that each and every day I am granted post-transplant is an incredible blessing.

The American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT), formerly known as the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, is a professional society of more than 2,200 healthcare professionals and scientists from over 45 countries who are dedicated to improving the application and success of blood and marrow transplantation and related cellular therapies. ASTCT strives to be the leading organization promoting research, education and clinical practice to deliver the best, comprehensive patient care.