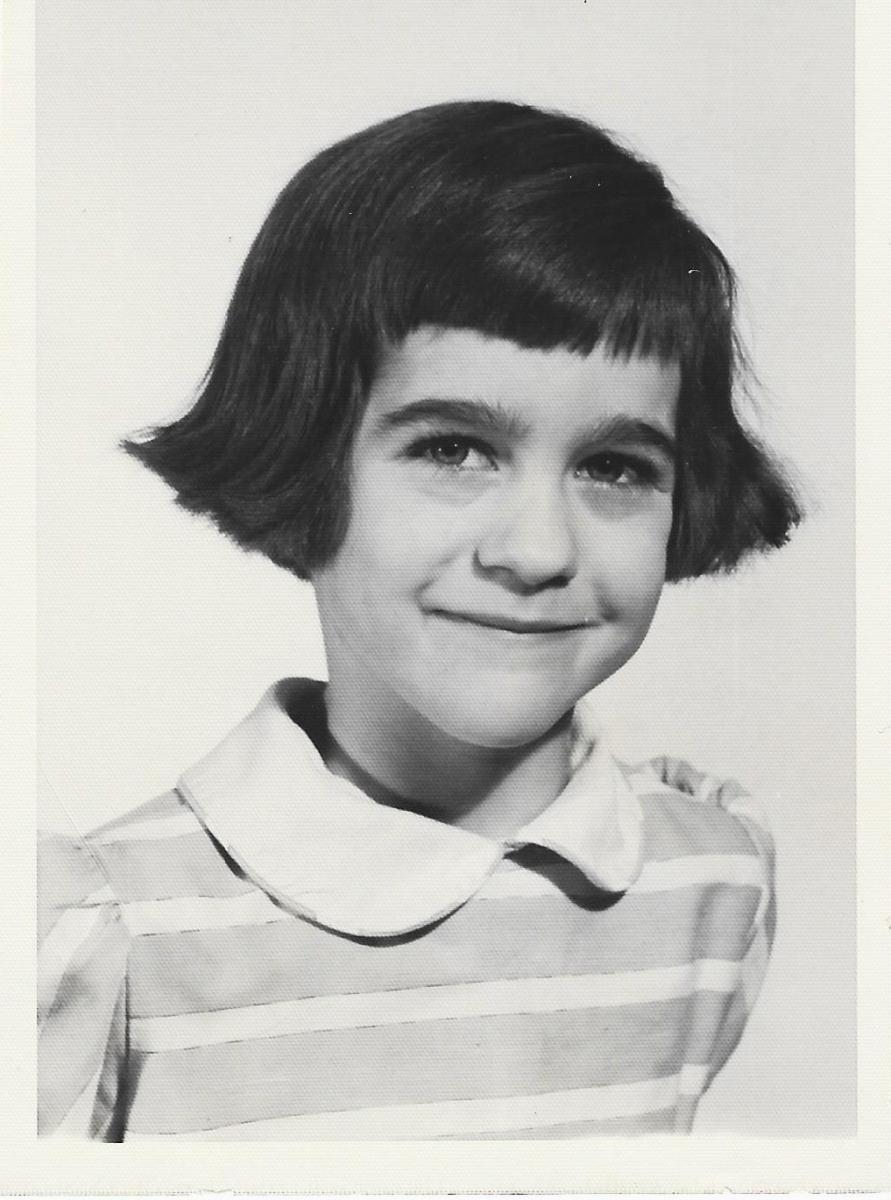

Nancy Lowry

When Nancy Lowry received the world’s first successful life-saving bone marrow transplant, she was six, she clarifies, not seven (as cited in some articles about her case). Though that detail might seem insignificant, in Nancy’s life precise timing has meant the difference between life and death.

In the summer of 1960, a young resident at the University of Washington Medical Center offered Nancy’s parents a thread of hope for their perilously sick daughter: a radical, and as yet unsuccessful treatment -- bone marrow transplant. Nancy, now in her 60’s, has only recently begun to recognize the true historic significance of her treatment and all the forces that conspired to land her in the right place, at the right time. As she describes it, “I really didn’t appreciate until last year that I was not only in the right city, at the right hospital, but also with people who knew the right doctors to call.”

Nancy, and her identical twin sister, Barbara, grew up with their parents, and their older brother George, in Tacoma, Washington. When Nancy was four, she developed a seizure disorder and, subsequently, aplastic anemia (from the seizure medications). Nancy remembers the appearance of her blood disorder as a dramatic and terrifying event: “I was laying on my brother’s bed. My mom was giving me ice chips because my gums were bleeding, then she suddenly gathered me up and took me to the pediatrician…. He looked at my arms and legs, I was covered with bruises. He picked me up off the table and carried me across the street to the hospital.”

Nancy, and her identical twin sister, Barbara, grew up with their parents, and their older brother George, in Tacoma, Washington. When Nancy was four, she developed a seizure disorder and, subsequently, aplastic anemia (from the seizure medications). Nancy remembers the appearance of her blood disorder as a dramatic and terrifying event: “I was laying on my brother’s bed. My mom was giving me ice chips because my gums were bleeding, then she suddenly gathered me up and took me to the pediatrician…. He looked at my arms and legs, I was covered with bruises. He picked me up off the table and carried me across the street to the hospital.”

From that small Tacoma hospital, Nancy was quickly transferred (in a non-traditional way!) to the UW Medical Center. As Nancy remembers: “My Aunt Gertrude – who was a take charge kinda woman, and like a grandmother to us -- decided I wasn’t going in an ambulance. She laid a mattress in back of her Pontiac Sedan, and she let me wear her pink pajamas. That was August 6th.”

The date was significant because, at the UW Medical Center, Nancy was given just a week to live. And this is where the saving grace of serendipity began. First, Nancy had the luck to be assigned to a gifted young resident, Dr. Moreno Robins. That very week, Dr. Robins attended a lecture for medical students by a visiting authority on the emerging science of transplantation, Dr. E. Donnall Thomas. Though he would go on to become the 1990 Nobel Prize-winning “father of transplantation,” on the day of his lecture Dr. Thomas presented a picture of transplant medicine that fell far short of its aims. He’d overseen or performed over a hundred bone marrow transplants, primarily on patients with leukemia, without producing a single long-term survivor.

gifted young resident, Dr. Moreno Robins. That very week, Dr. Robins attended a lecture for medical students by a visiting authority on the emerging science of transplantation, Dr. E. Donnall Thomas. Though he would go on to become the 1990 Nobel Prize-winning “father of transplantation,” on the day of his lecture Dr. Thomas presented a picture of transplant medicine that fell far short of its aims. He’d overseen or performed over a hundred bone marrow transplants, primarily on patients with leukemia, without producing a single long-term survivor.

Dr. Thomas shared that the few patients who’d done best, in the short term, were those who received a “matched” donation from a sibling twin. After the lecture, Dr. Robins approached Dr. Thomas to say, “We have a child upstairs who has an identical twin.”

All at once, for Nancy, a girl just shy of her seventh birthday who’d been given only a week to live, a small door of hope swung open.

Nancy notes that, “Even though we were only six, doctors asked Barbara for her permission to use her marrow. She thought they were going to take it all, and she said, ‘No thank you.’ They explained and she agreed… The day after the donation, she was surprised to find that her arms and legs still worked, she was surprised to still be the same person!”

Nancy’s transplant took place on August 12th, 1960. At the end of August, she and Barbara turned seven, together.

Barbara’s bravery, in agreeing to give her twin such a frightening-sounding gift forged an obvious, lasting bond. Nancy says she and Barbara remain exceptionally close, these many years later, and live just over an hour apart.

Barbara’s bravery, in agreeing to give her twin such a frightening-sounding gift forged an obvious, lasting bond. Nancy says she and Barbara remain exceptionally close, these many years later, and live just over an hour apart.

Nancy’s story, as much as it’s a story of luck beginning with her birth as an identical twin, is also a story of perseverance in the face of defeat. It’s a story, finally, of the pioneering spirit of those few doctors who persisted – even as they witnessed staggering heartbreak – in extending medicine’s healing reach to the patients they fervently hoped to save.

Still, Nancy did not grow up seeing herself as a medical miracle or exceptional survivor who helped break ground for the many thousands of lives saved after hers. She grew up with snippets of a story, hazy early-childhood memories, and above all the edict to Move on! As Nancy explains, “Even though I almost died, the idea back then was to let it go. Enjoy life, appreciate what you have! Now, I feel I can really own this experience, I’ve done a lot of research and can see all the dangers I dodged.”

Later in life, when Nancy began to research her transplant and the many failures of early transplant history, she was struck with sorrow, and with the guilt many survivors carry, “I found articles where they [family and friends] celebrate the patients coming home, but then they died… And that’s when I truly appreciated that the success of my transplant came at a cost, and that cost had been paid by all those people who came before me.”

Nancy recognizes her luck in the same straightforward terms. “If I had not been in the Seattle area, where Dr. Robins and Dr. Finch (the doctor who invited Dr. Thomas to speak) were, and if I had not had an identical twin…“ Nancy’s voice trails off. The rest, unsaid, is obvious.

is obvious.

But she was in Seattle, and Dr. Robins did attend Dr. Thomas’ lecture, and Dr. Thomas did agree to lead Dr. Robins through his innovative protocol. And Nancy is here, on the other side of a decades-long career as a nurse serving children with special needs. She’s here, telling her story. Both a beacon of hope and a part of history, alive and well.

We can imagine Dr. Thomas’ joy in Nancy’s life – and in the thousands of survivors who came after her. And who, like Nancy, lived to tell their stories, and love their circle of people, because they found themselves in exactly the right place, at exactly the right time. Dr. Thomas invented that ‘right place, right time’ for Nancy and, ultimately, for so many. Those of us grateful for his work are legion.

The American Society for Transplantation and Cellular Therapy (ASTCT), formerly known as the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation, is a professional society of more than 2,200 healthcare professionals and scientists from over 45 countries who are dedicated to improving the application and success of blood and marrow transplantation and related cellular therapies. ASTCT strives to be the leading organization promoting research, education, and clinical practice to deliver the best, comprehensive patient care.

Photo Credit: Brittney Corey brittneycorey.com